This week, I thought I’d make you a list of great wizards in literature.

You’re a list of great wizards in literature!

More seriously (but still not completely), and in approximate order of ancientry:

1) Merlin

First appearance in (written) literature: 1136, i.e. Before English, courtesy of Geoffrey of Monmouth, who turned him from Welsh into Latin. Best known for his connection with King Arthur.

My favourite incarnation is in T.H. White‘s The Sword in the Stone (1938). Enchanted tea-things that wash up after themselves? That’s my kind of wizard. “Let’s dunk the teapot!” Also sound on tiggies.

2) Gandalf

First revealed to the reading public in 1937, in Tolkein’s The Hobbit.

The very epitome of the wise elder, with his robes, his shabby hat, his staff, and his contributions in the area of entertaining explosions.

“I – am an enchanter…. There are some who call me – Tim.”

Literature might be stretching the point slightly in the case of Monty Python‘s 1975 creation, but movies are stories too – let us not be snobbish.

He also is skilled in the area of explosions (if not so decorative as Gandalf’s) and warns the Holy Grail-hunters of the perils of the killer rabbit. “Death awaits you all with nasty big pointy teeth.” Indeed.

The Librarian has been part of Sir Terry Pratchett‘s Discworld since the beginning: The Colour of Magic in 1983. It was not until 1986 (The Light Fantastic) that he took on his present form: that of an orangutan.

Devoted to his books and his bananas, he has a strong sense of justice, particularly when it comes to people who refer to orangutans as ‘monkeys’. You Have Been Warned.

5) Questor Thews

The court wizard of the Magic Kingdom for Sale by Terry Brooks, he has been in circulation since 1986.

Questor is a very relatable wizard: like so many of us, he tries his best in some tough situations, and sometimes his best isn’t good enough. The court scribe is a Wheaten Terrier for this very reason.

6) The Bursar aka Professor A.A. Dinwiddie, colleague of the Librarian. First introduced in Sir Terry’s Faust Eric, published 1990, he is a mild and harmless fellow who has lost his sanity in the dog-eat-dog world of wizardly politicking. Fortunately, a precisely calibrated dose of dried frog pills (for recipe see here) causes him to hallucinate that he is sane. And occasionally that he can fly.

7) Professor Dumbledore first saw the light of day in J.K. Rowling‘s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (1997).

Full disclosure: I haven’t read all the books and I do not know all his tale. But this was enough to make me like him: “I would like to say a few words. And here they are: Nitwit! Blubber! Oddment! Tweak!” Brilliant.

8) Derk

Here is the example par excellence of how a talented writer can parody the clichés of a genre without alienating readers who enjoy that genre: Diana Wynne Jones‘ The Dark Lord of Derkholm, published 1998.

Personally, I love the sequel, The Year of the Griffin just as much, if not more. Derk specialises in genetics, which is why he and his wife have seven biological children, five of whom are griffins.

9) Woodward**

Woodward came into existence sometime in the early 21st century – darned if I can remember precisely when – and is currently pulling strings in my WIP, Tsifira.

In appearance he is much like a dandelion – raggedy green with a fluffy white head – but he has spent the last 15 years disguised as a gardener who only ever says “Eh.”

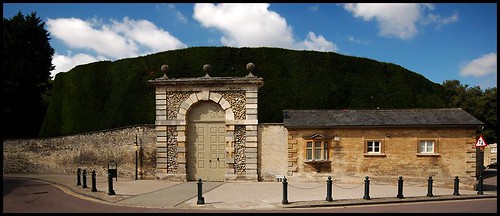

In this disguise he keeps an eye on the growing princess and tends the ensorcelled privet hedge he planted to protect her. But he knows he can’t keep her safe behind the hedge forever.

So there you have it! It was going to be The Top Ten but I could only think of nine and it seems like a more wizardy number in any case.

It may be that this list of ‘Greats’ is more a list of my favourites – so who did I miss? Who are your favourites, and by whose hand?

All comments welcomed; only spammers will be turned into frogs.

Your obedient servant,

Sinistra Inksteyne

* for a given value of “great,” i.e. obtaining and retaining my affection and/or interest

** formerly known as Wentworth; he underwent a name-change between drafts.