Most refugees never become famous at all, seen simply as part of a sea of faces. Very occasionally someone becomes famous for being a refugee. But there are times when someone becomes famous and people simply forget that they ever were a refugee.

I don’t suggest that being a refugee should perpetually define anyone. But it’s as well to remember that refugees aren’t only those people, they’re these people as well.

Take, for example Jesus, Mary & Joseph, who fled Roman-occupied Israel for Egypt when Jesus was only a tiny tot. The wise men from the East having inadvertently outed the baby as “born to be king of the Jews”, he was squarely in the sights of Herod the (so-called) Great – whose paranoia about takeovers was so strong that he had, at various times, had his mother-in-law, wife, and three sons whacked. Just to be on the safe side, Herod issued an order that all the little boys of a likely age in the region where Jesus was born should be exterminated… but Joseph had been warned and so Jesus escaped.

Take, for example Jesus, Mary & Joseph, who fled Roman-occupied Israel for Egypt when Jesus was only a tiny tot. The wise men from the East having inadvertently outed the baby as “born to be king of the Jews”, he was squarely in the sights of Herod the (so-called) Great – whose paranoia about takeovers was so strong that he had, at various times, had his mother-in-law, wife, and three sons whacked. Just to be on the safe side, Herod issued an order that all the little boys of a likely age in the region where Jesus was born should be exterminated… but Joseph had been warned and so Jesus escaped.

Moving forward with a leap to the twentieth century (hup!) we get to a fictional family (also Jewish) living in Russia. They also fall foul of a powerful ruler – in this case, Tsar Nicholas II – and are driven out amid a backdrop of state-sponsored pogroms. Sounds like a cheery subject for a stage musical, doesn’t it? Tevye and family, from Fiddler on the Roof.

Speaking of stage musicals, the Von Trapp family appear on both fictional and non-fictional lists, The Sound of Music being somewhat fictionalized. Driven from occupied Austria by the Nazis’ plans for Captain Baron Von Trapp, they took refuge in America, but their experiences undeniably left marks on the family. (Have a read about them; theirs is a fascinating story.)

Hopping backward in time slightly – and moving back into the purely fictional realm – we have Monsieur Hercule Poirot. It isn’t often brought up, but he initially comes to England as a refugee during World War I. His first appearance is in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, wherein he investigates the murder of the wealthy woman who has given a home to him and his compatriots. After the war, he stays on… and, of course, thrives.

Hopping backward in time slightly – and moving back into the purely fictional realm – we have Monsieur Hercule Poirot. It isn’t often brought up, but he initially comes to England as a refugee during World War I. His first appearance is in The Mysterious Affair at Styles, wherein he investigates the murder of the wealthy woman who has given a home to him and his compatriots. After the war, he stays on… and, of course, thrives.

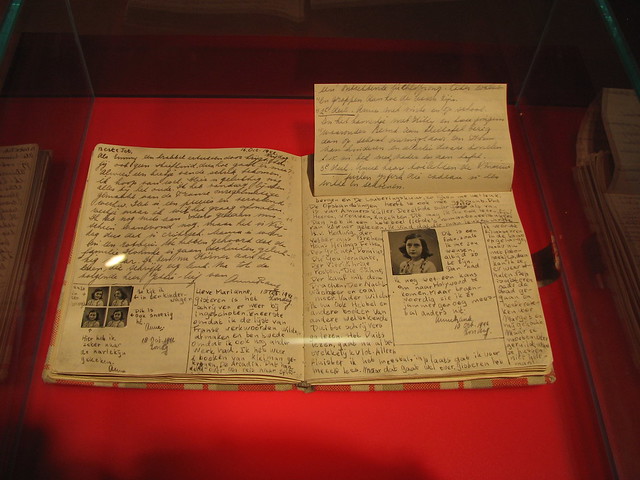

Alas, the real refugees were not always so lucky. The Frank family fled Germany for the Netherlands when the Nazis came to power, but in due course the Netherlands too were invaded. They tried to escape again, to the USA, but doors closed in their faces: they were Germans, and therefore suspect. After all, the government reasoned, with family still in Nazi Germany, they might be able to be blackmailed into acting as spies. So the Franks remained in the Netherlands, until they were sent away to the concentration camps.

Others were more fortunate. Albert Einstein was already in the USA on academic business when Hitler came to power, and sensibly decided to stay where he was. For a refugee, he was a many-stated man: his citizenship listing on Wikipedia has seven listings (including, admittedly, “stateless” for five years) and he was offered more.

Another who took refuge in the USA was Conrad Veidt. A popular film actor, he was not himself Jewish, but when compelled to state his race for the authorities, he put down “Jew” – because his new wife was Jewish. (Goebbels: He will never act in Germany again.) Veidt and his wife then fled to Britain, and subsequently, when it appeared Britain was in danger of invasion, to the US. He kept busy appearing in anti-Nazi propaganda films, but died suddenly (golfing heart-attack) in 1943.

Another who took refuge in the USA was Conrad Veidt. A popular film actor, he was not himself Jewish, but when compelled to state his race for the authorities, he put down “Jew” – because his new wife was Jewish. (Goebbels: He will never act in Germany again.) Veidt and his wife then fled to Britain, and subsequently, when it appeared Britain was in danger of invasion, to the US. He kept busy appearing in anti-Nazi propaganda films, but died suddenly (golfing heart-attack) in 1943.

Peasants, singers, scientist, actor, diarist, detective, Messiah… The next time you see a mention of refugees in the media, try to see past the sea of faces to a single face, and wonder who they are beyond “refugee” – and who they might yet live to be.