All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.

J.R.R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring

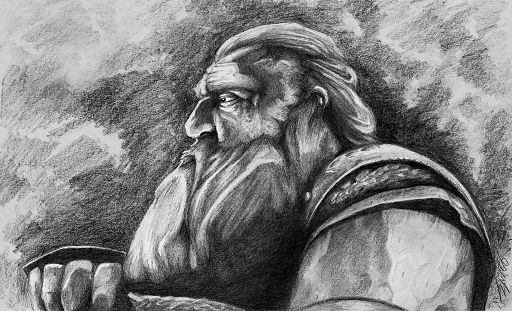

Nine Dwarves of Story and Song

More or less. Well actually, more, as when Gandalf went to visit Beorn with “a friend or two…” In historical order, as with the list of varyingly great wizards of literature.

1) Oldest of all are the seven companions of Snow White, committed to paper in the early nineteenth century. I shall not give their names, mostly because they were given no names in the tales set down by the Brothers Grimm. And also because they have been given far too many names in the many years since – see here if you don’t believe me. They seem to have been the origin of the literary convention that dwarves are miners: they “lived among the mountains, and dug and searched for gold.”

2) Next up are that very band whom Gandalf introduced to Beorn in such drawn-out fashion. Thorin Oakenshield and his twelve companions: Dori, Nori, Ori, Balin, Dwalin, Fili, Kili, Oin, Gloin, Bifur, Bofur and Bombur. They made their literary debut in 1937 in Tolkien’s The Hobbit – which next year will celebrate eighty consecutive years in print. Like their predecessors, they are keen on mining and gold. This is a point of contention with dragons, since they also like gold, and no one wants to share.

3) Trumpkin! Possibly you were expecting a certain someone from The Hobbit‘s famous sequel, but no. Tolkien’s friend Professor Lewis published Prince Caspian in 1951, thus introducing the world to this practical-minded, rather sceptical dwarf who doesn’t believe in magical talking lions and all that sort of thing – at least until he meets one. After helping Caspian claim his rightful throne, he later finds himself the de facto ruler of Narnia as Lord Regent when Caspian sails away on the Dawn Treader.

4) And now, the dwarf you’ve all been waiting for – for the last paragraph at least – Gimli son of the aforementioned Gloin. Notable as the only dwarf in the celebrated Fellowship of the Ring (in the book of that name, published 1954), he is very good with an axe. Possibly the dwarf-axe link descends from the use of pickaxes in mining; I’m not sure. Frankly, I wouldn’t want Gimli coming at me with any kind of axe, picky or otherwise, but he’s a great person to have at your back in a fight. He has one of my favourite lines from Tolkien’s whole oeuvre: “Faithless is he that says farewell when the road darkens.” Gimli doesn’t.

Gimli is also possibly the first dwarf to fall in love with an elf, since a purist would not count the fan-fictionesque flirtation of the lately inserted Tauriel with the aforementioned Kili. Gimli’s chivalrous devotion to the Lady Galadriel is made of entirely different stuff, and I must say I prefer it.

5) Hwel the playwright is a Discworld dwarf, and a rather unusual one: he doesn’t like being underground. This makes a career in mining problematic, and he instead becomes a playwright attached to Vitoller’s theatrical company. Imagine a rather smaller version of Shakespeare who has all the ideas of time and space trying to squeeze into his skull at once, and you have a fair idea of Hwel as he appears in Wyrd Sisters (1988). He knows what it’s like to be unable to get what’s into your head onto the page, and that gives me a bit of fellow-feeling for him.

6) Also in 1988 is the only non-literary dwarf on the list, Willow Ufgood, who has the distinction of being in a story named after him, and not after someone bigger, as is the usual fate of dwarves in fiction. He is the main character of the film Willow, the story for which was written by George Lucas. He is also a candidate for the list of wizards, although his magical efforts are not always successful. (Turning a troll into a gigantic two-headed fire-breathing monster is not recommended for the beginner.) As with so many dwarves on screen, he is played by Warwick Davis.

7) Cheery Littlebottom is the first openly female dwarf in the Discworld. (That’s her on the right, with the beard.) She was introduced in Feet of Clay (1996) and has since been promoted to the rank of Sergeant in the City Watch. She likes makeup and sequins and wears dresses – off duty, of course. She has also welded heels onto her uniform boots and has been known to attend functions with a little evening axe in a clutch purse. She is, after all, a dwarf.

8) Ruskin introduces himself in Diana Wynne Jones’ Year of the Griffin (2000) as “Dwarf, artisan tribe, from Central Peaks fastness, come by the virtual manumission of apostolic strength to train on behalf of the lower orders.” By which he means that he has run away from the Central Peaks mines in which his class is enslaved, in order to get wizarding training (alongside Elda the titular griffin, daughter of Derk) so that he can help his comrades overthrow the status quo under which they are being oppressed. He is, in fact, a revolutionary. And while he can trade long words with the best of them, he is by no means averse to letting a bit of the hot air out of the speech of those who oppose him.

9) Malin is, like Woodward, one of my own imagining, who has yet to see the light of publication. He likes to think of himself as a pessimist, but his actions give him the lie. He goes on fighting for his people’s freedom long after they themselves have given up, given in, and ostracized him as a troublemaker. Creative, chaotic and proud to be a thorn in the side of the powers that be, he first appears on the scene in a prison cell – a repeat engagement after his earlier escape.

There you have it – nine (or possibly twenty-seven) of my favourite literary dwarves. Feel free to add yours to the list!

Read It Again!

Thus goes up the cry from many a small child, with their insatiable desire for the same bedtime story to be told, over and over (and over) again.

But it’s not just little kiddies who do it. Scratch a reader and you will find a re-reader – but what is it we’re re-reading? And why?

The winner of the gold medal, blue ribbon and all-around first prize for re-reading (re-readiness?) is the Scriptures; unsurprising given the emphasis so many traditions put on reading, re-reading, memorizing and internalizing the words of God. As Jesus said, these are “foundational words, words to build a life on.” But, leaving the Scriptures aside, as the best-seller lists do (since the same book invariably tops the list), what are the most popular re-reads?

The comments on this post reminded me of the widespread passion for re-reading The Lord of the Rings – and not just re-reading it, but re-reading it again every year. That’s dedication, especially if you aren’t a fast reader.

Some people re-read other classic novels such as Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice or Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, although I have yet to hear of anyone who repeatedly reads War and Peace – apart from Countess Tolstoy, who apparently recopied and edited it seven times. That’s going above and beyond the call of duty, it seems to me. Bearing thirteen children is one thing; reading War and Peace seven times is quite another.

Many people obsessively re-read C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia as children, and some continue the habit. I myself, as a child, re-read pretty much everything I could get my hands on, as I was a voracious reader with limited (re)sources. I even read our children’s encyclopaedia by the volume (Vol. 1, Article 1: Abbey, which may be connected to my subsequent interest in all things monastic).

More recently, I have noticed a pattern to my re-reading. When I am tired and want to relax, I read either an old favourite – Agatha Christie, Patricia Wentworth, Ngaio Marsh, Ellis Peters – or a book by an author with whom I am sufficiently familiar to be sure I will enjoy the book. And yes, this means that when I want to relax I almost without exception curl up with a mystery (although I did curl up with The Curse of Chalion the other day).

When I am not in need of book-induced relaxation – when I have more mental energy – I tend more toward the reading of non-fiction. Books about writing, books about whatever I have an interest in at the moment, books which happened to show up in an old box from someone’s grandmother. Reading entirely unfamiliar fiction doesn’t happen as often, unless the book is very compelling when I glance into it, because it doesn’t fit into either of my two settings: Relax or Absorb Information.

But once I’ve read a non-fiction book, I seldom feel the inclination to re-read it, and I think this reveals something about why people re-read – or at least why I re-read. I re-read books because there is something in them which I cannot fully obtain from one reading. If it’s non-fiction, it’s because I didn’t absorb enough of the information it contained the first time round.

With fiction, that doesn’t apply. I mean, look at the enormous popularity of P.G. Wodehouse’s novels. Read one, you’ve got a pretty good idea of them all, but that doesn’t stop people reading the rest and then re-reading them. Because the essence of the book isn’t in the facts of it, it’s in something altogether more evanescent. The style of the book, or perhaps its soul. You can’t break that down to its component parts to analyze why it works. The letter kills, but the spirit gives life, you could say.

Or, to steal a structure from Maya Angelou, people will forget what the book said, they’ll forget what the characters did, but they will never forget how the book made them feel. And that, I am convinced, is the secret of all re-reading. Reading the book produced in us a feeling – and with great books it’s a feeling no other book creates – and re-reading the book is the only way to feel that again. This is how reading prescriptions work; and also why we have fan-fiction.

What do you think? What books do you re-read, and why?