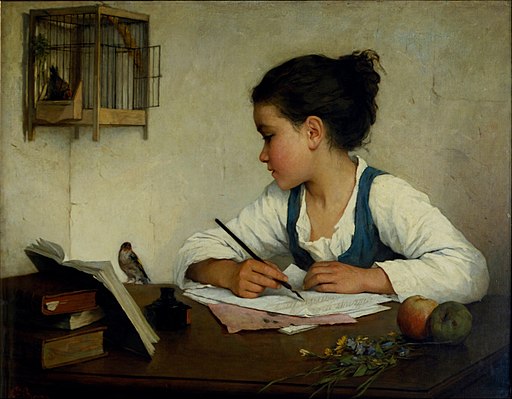

Thus began my first attempt at a written chronicle of my day-to-day life. I was twelve years old, which may account for the style. Or, then again, that might just be me.

I pursued the theme, off and on, for years. Jo Brand says that she re-reads her diary occasionally “to remind myself what a miserable, alienated old sod I used to be.” I don’t re-read mine, for similar reasons. I was probably only miserable a minority of the time, but that minority formed the majority of the time I wrote in my diary. When I was happy, I was too busy enjoying myself to bother telling an exercise book about it.

More enjoyably, I kept a joint diary with a friend for some time. We had two exercise books, and swapped them once a week, read what the other had written, and had a jolly good go at solving the problems of the universe together.

Once the circumstances of life drove us to different countries, my diarising became very intermittent, until I left university and suddenly found myself craving the word fix. The diary from that year is not so much miserable as simply too boring to re-read, although I’ve considered trying it as a remedy for sleeplessness.

The following year I moved to Wellington to study scriptwriting, which solved the word fix problem; but, being away from everyone I knew, I kept talking to the diary anyway. (Back to the miserable setting, alas.)

Then the Caped Gooseberry and I started our long-distance courtship, and I gave up writing a diary, because why rewrite in a book what one has already typed out in an email? As I was unemployed that year (overqualified for any job I could do, underqualified for everything else), I sent a lot of emails. Certainly not miserable, but probably boring to any but the starry-eyed correspondents themselves.

Then I got a job, got engaged, and moved cities (all in a matter of weeks), which left me learning the new job full-time, planning a wedding and filling in weekends at a writing initiative in another city. Re-starting a diary somehow failed to make it back on to the To Do list. It wasn’t until a year or so later, when my spiritual director suggested I read The Artist’s Way, that I started regularly diarising, or journalling, or whatever you call it.

The early ‘morning pages’ read largely as repeated rants about how cold it was – I used to get up half an hour early for this – and how much I wanted to leave my job. (By now an experienced diarist, I was capable of being both miserable and boring at the same time.) Then I started blogging, and soon after had the idea to actually do the Artist’s Way exercises, over the course of a year. Which I did, more or less, blogging about it as I went. Luckily for the reading public, I never blogged the morning pages.

But by the end of that year, the morning pages had turned into a sort of spiritual diary. Largely, to be fair, me ranting at God, but then, God likes people to talk to him, even if all they do is yell. I think those early morning scribbles kept me sane, or at least out of depression’s grip. It seemed some days that was the only thing worth getting up for, and the only thing that could bear me through the day. I had to keep it up.

Once I left my job, I carried on with it, albeit at a much more civilized hour of the morning. (If God had intended humans to rise before dawn, he would have made us able to see in the dark.) I generally write in it six days a week, and sometimes include what’s been happening in my outer world, particularly when it affects my inner world.

No-one reads it but myself and occasionally the Caped Gooseberry. Oddly, considering that it’s a place for being honest with myself about deep and sometimes difficult things, it’s actually an enjoyable experience to re-read, unlike the “what I did today” diaries – or more accurately, the “what I felt about what I did today” diaries. Neither miserable nor boring – who’d have thought I had it in me?

I keep three other diaries, to my surprise; or rather, two diaries and an annal.

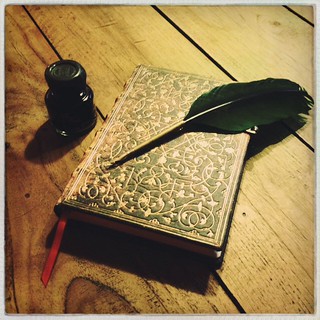

One is the record of my writing work, written in a paperblanks week-at-a-time diary (a Foiled Mini Horizontal with a magnetic closure, if you’re a stationery junkie like myself). I keep track of what I worked on each day, as far as both the current Work In Progress and this blog are concerned. I also note other matters of writerly importance, such as how often the fountain pen requires refilling (a good indicator of how much writing I’m getting through) and when I buy ink, or a craft book.

The second diary only dates from the beginning of this month, and I am writing it on the computer – I really don’t know why. Why on the computer, that is. I’m not quite weird enough to write a diary without knowing why. It’s a very specialized diary, and I promise to tell you all about it – some other time. (It pleases me to be mysterious about the prosaic. Bear with me, I beg you.)

The annal is one which the Caped Gooseberry and I keep together. The book which houses it was a gift from my comrades at the DDJ – a beautifully bound blank-paged book in which, each anniversary, we sum up the happenings of the previous year. It is sometimes disturbing to look back and see how much one has forgotten, even of the ‘highlights’. Forgetting the photos which are taken at the same time is, in my case, a matter of self-defence – I am most decidedly not photogenic.

To finish on a completely random note, if you are looking for a fictional diary to read, I can highly recommend Catherine, Called Birdy by Karen Cushman. A cut (or indeed, a whole slice) above the usual run of historical-fictional teenage girls’ diaries, and very funny to boot. This is one of those books where the reader becomes incapacitated with laughter and the book has to be passed around the room. (This is the voice of experience.)

Sadly, I fear posterity will find no such hilarity in my diaries, should I unaccountably fail to have them destroyed before I die. Posterity: consider yourself warned.