Believe me, they ain’t got nothing on the eighteenth-century Romanovs ruling Russia.

Of Alexei’s two surviving sons (one with each wife), the elder, Ivan, had “serious physical and mental disabilities,” as Wikipedia tactfully puts it. The younger, Peter, was only 10. Add to this the fact that each of their mothers came from a different clan, and therefore each son had a different political web surrounding him. Solution: have them both rule as co-tsars (where there’s a will, there’s a way, right?). And since neither of them was in a fit condition to actually rule, Peter’s mother (wife #2 of Alexei-who-started-all-this) was to be regent.

And now he could rule? No! His mother was still in charge. She got him married to a woman he didn’t care for, and three sons later, he had her (the wife, not his mother) packed off to a convent too – conveniently dissolving their marriage and leaving him free to marry his new squeeze.

It was no joke being married to a Tsar in those days. Customarily, a bride was selected by means of a bride-show, which is exactly what it sounds like, only without all the cheesy “Bachelorette Number 3!” stuff. Round up a few good-looking aristocratic girls, stand them in a row, and let the Tsar pick one.

Ivan V’s wife Praskovia, chosen the old-fashioned way, was a good, sensible sort of woman, and they got on very well together. Yes, her husband had health issues by the yard, but at least he wasn’t frolicking with mistresses or forcing her to become a nun, so all things considered, she lucked out – and she was treated with great respect by the court generally, Peter included.

Peter himself had moved on to Wife #2: Catherine. Actually, she started out as an illiterate Polish peasant girl called Marta, but she was so extraordinarily good-looking that within two years of Russian troops moving into the town where she lived, she had moved into Peter’s palace and given birth to his son.

She took the name Catherine, and secretly married Tsar Peter in 1707, by which time she had presented him with three children. Five years later they got officially married (five children by this point), and they eventually had twelve children together, including three Pyotrs and three Pavels, as they followed the custom of re-using the names of children who died young.

Ivan V died in 1721 at the age of 29, leaving a wife and three surviving daughters. Now Peter could rule entirely by himself in name as well as fact. This only lasted till 1724, when he appointed Catherine his co-ruler as Catherine I. He then died the next year, leaving her to rule alone until she herself died in 1727. Illiterate peasant girl to illiterate Empress and Autocrat of All the Russias – now that’s social climbing. (Eat your heart out, Eva Perón.)

By this point, the Romanovs were running low on sons. Ivan had only had daughters, and of Peter’s eight or nine sons (I am not even kidding; the ninth is of disputed existence), none were now living.

However, his eldest son, Alexei, had managed to produce a son before he died (under torture – I told you this family makes yours look normal), so this son now became Tsar Peter II. He died three years later on what would have been his wedding day. He was fourteen.

Now, of course, they were really at a loss, as they had completely run out of male descendants. Women, women everywhere, as far as the eye can see – including the daughters Peter the Great had had with Catherine before they got married, as he had retrospectively legitimized them. (Tsars: Can They Time-Travel?) But which woman to pick?

The council responsible settled on Anna, one of Ivan V’s daughters. Why her? Because she was born legitimate, and unlike her older sister Catherine, she had experience of governing (having ruled her late husband’s duchy for twenty years, after he died a few weeks into their marriage). Plus she didn’t have any pesky foreign relatives who might try a grab for power or interfere with foreign relations. Of course, this was only a temporary fix to the inheritance problem as Anna was childless.

But when Empress Anna died, Anna-the-mother-of-Ivan had herself made Regent, as Ivan VI was only two months old. She was so profoundly unpopular (people complained she spent all her time reading novels in bed and dealing with her complicated love life) that within a year her regency was overthrown and she was imprisoned.

Of course, this was rather hard on Ivan VI, whose tsardom was overthrown at the same time. He was sent to imprisonment in one fortress, despite being barely old enough to walk, and his parents were imprisoned in another.

Not officially having children, however, her heir was the son of her older sister Anna: Peter III. (Like Peter II, he was also a grandson of Peter I, “the Great.”) He came to the throne in 1762, and also departed it in 1762, when it was pinched by his wife. (This was not a good marriage. She had three children, one or two of whom may have been his.)

Who has ever heard of Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst? No one. Catherine the Great? Well, that’s a different story – but the same woman. After six months of her husband’s rule, she staged a coup, and he was forced to abdicate – and shortly afterwards he died, although it is not clear how. It’s a fair bet it wasn’t of natural causes.

It may seem odd that Catherine managed to snag the throne of Russia when she herself wasn’t even Russian, but Peter III wasn’t all that Russian either, having been born and raised in his German father’s princedom and barely even speaking Russian.

But what of Ivan VI? Wouldn’t he have a better claim than Catherine? You bet your boots he would. He had a better claim than a lot of people, which is why he was still a prisoner. Peter III had treated him kindly (without releasing him: let’s not get carried away here), but Catherine gave orders that if any attempt was made to rescue Ivan, he was to be killed – better safe than sorry. He therefore survived only two years into Catherine’s reign, dying in Shlisselburg fortress at the age of 23.

Catherine II died in 1796, having ruled for 34 years. She was succeeded by her son Paul I, who may well have been the son of her husband. He had been taken off her more or less at birth by her husband’s aunt, the Empress Elizabeth. Unsurprisingly, he had a rotten relationship with his mother, and idolized his dead father – who he now had dug up and buried in a more tsarly manner. On the other hand, Paul wasn’t much liked, either, and so he was assassinated after five years on the throne. (Court doctor: it was apoplexy! Swords were not involved in any way!)

However, though his first wife had died in childbirth with her first child, he and his second wife had ten children, three of whom were at different times called Emperor of Russia (though one never actually ruled).

The line of Ivan V, elder half-brother of Peter the Great, had finally died out. The ‘Petrine’ line of Romanovs would continue ruling Russia until 1917.

From 1701 (Tsars: Peter “the Great” I and Ivan V) to 1801 (Tsar: Paul I) there were ten emperors/empresses, covering a mere four generations: Paul I was the great-grandson of Peter I. (Assuming, of course, that he was the son of Peter III…)

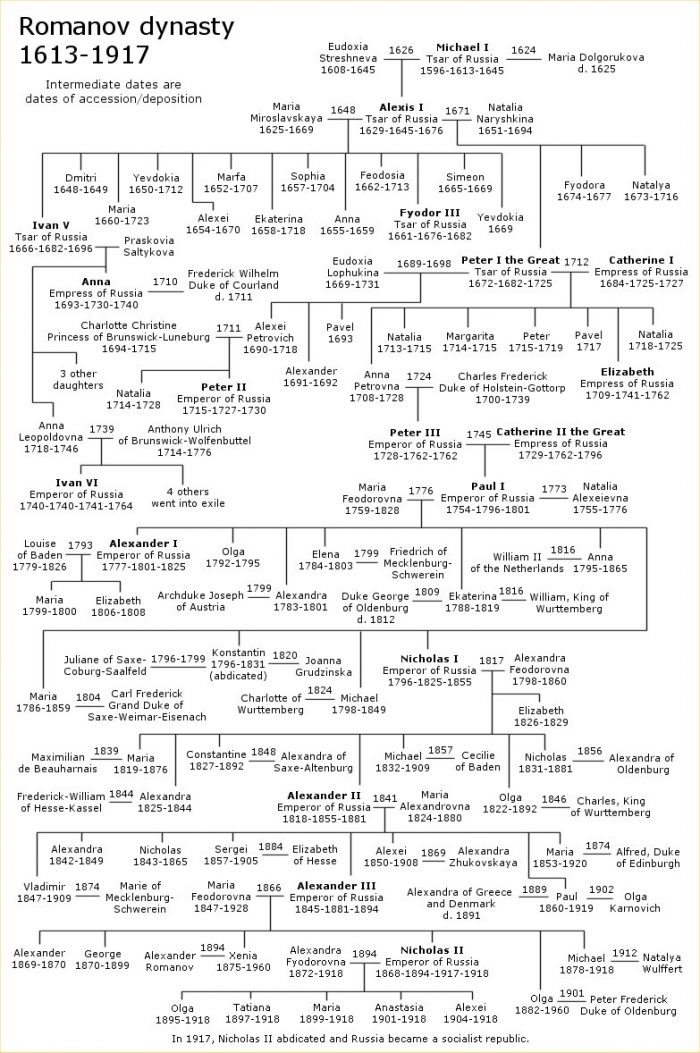

And now, what you’ve all been waiting for: a family tree to make this all a bit clearer.

Alexei, with whom we started this story, is in the second line; Paul I is halfway down, on the right. As for the second half…. well, that’s another story.