I feel rather sorry for those who had to live under the French Revolutionary Calendar. Imagine making it through the months of Mist and Frost, only to have Snowy, Rainy and Windy to look forward to! Not to mention the rather unpleasant idea of having to work nine days before you get a single day off.

So when it came to the world-building task of creating a calendar for Restoration Day, I knew some things I wanted to do, and some things I wanted to avoid. Like the Jacobins, I created a round of months which reflected the natural world. Unlike the Jacobins, I had more sense than to try to introduce decimal weeks.

The Arcelian calendar begins with spring: Grenian (greening), Blosse (blossom) and Molsh – time to fork some mulch onto the garden before the summer heat comes and dries everything out. Summer starts, you see, with Sunnen and ends with Dryden, with Hayen in the middle. Autumn brings Hærfest (time for a party!) followed by Sere (as everything withers) and Misth (you can tell winter is around the corner, can’t you?).

Unlike the Jacobin calendar, the winter months focus less on the doings of the dismal weather, and more on the doings of the people. The first month of winter is Prunen, followed by Diggen, which brings us at last to Budd, holding out the promise of the green of spring returning at last.

I had considered relating these months to the months of the Gregorian calendar, but then it occurred to me that my readers span both hemispheres and Confusion Is Liable To Result.

I had considered relating these months to the months of the Gregorian calendar, but then it occurred to me that my readers span both hemispheres and Confusion Is Liable To Result.

In the northern continents, for example, it is now Hayen, a time of hotness and dry grass. Down here in New Zealand, hotness is exactly what it isn’t, and as for dry grass, the last time I saw the cat bound across the back yard, it was like watching a skipping stone – splash, splash, splash.

No, down here it is Diggen time, although due to being rather behindhand with the gardening (I don’t like to go out when it’s raining, which is often), we are still at work on the pruning. Not the getting-rid-of-unnecessary-stuff-around-the-house kind of pruning, the actual pruning kind of pruning, with chopping off of branches and the like.

This year’s big effort is on the grapevine, a lordly, shed-eating monster which I suspect had not been pruned in years if not decades. To give you an idea of its size: the Google Earth image of our property does not give any indication that that shed exists. As far as the satellites are concerned, there is nothing but grapevine.

It not only covered the roof of the woodshed, it hung down on all four sides. Obviously, time for a haircut, preferably one that left the grapevine fruiting in places we could reach. Enter the ladder, the loppers and the secateurs. Also, to my surprise, the bucket and trowel.

Things which I did not expect to find in the grapevine:

> loop-de-loops and pretzels of blackened branches which had not seen the sun in years

> a thick layer of loam (the remains of years or decades of rotted-down leaves and grapes)

> earthworms (some white and squirming in the unaccustomed light)

> root systems (yes, some of the branches were putting down roots into the compost. I didn’t even know grapes could do that.)

> snails and slugs (some quite enormous)

> wetas (several)

> literally hundreds of slaters/woodlice and Things With Legs (did you know that slaters aka woodlice are crustaceans? Like lobsters. It does not make me loathe them any less.)

> and a large spider (only one, mercifully. Possibly a black tunnel-web spider, but I think I shall call it a cabochon spider, for its thorax and abdomen were round and smooth and tastefully coloured, at least until I beat it to a pulp with the trowel. After that, not so much.)

After digging up all that, I wouldn’t have been that surprised if I found a lost civilization or the portal to another world in there.

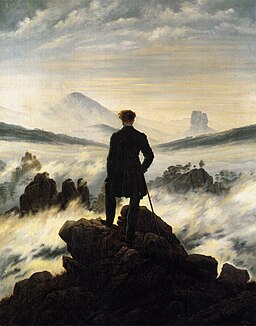

As you can imagine, this was no mere light afternoon’s gardening. I was three afternoons in before the difference was even discernible. But I persevered for two more solid afternoons, and, like Gandalf before me, “Ever he clutched me, and ever I hewed him… I threw down my enemy, and he fell from the high place and broke the mountain-side where he smote it in his ruin.”

Half the yard is now covered in the monster’s remains (unlike the mountain-side, our land is too squishy to break), and on the other half, two hills of grape-compost stand, ferried there in buckets by my Dearly Beloved.

Job done. At least until my aches fade sufficiently for me to tackle the apple, the redcurrant, the lemon and the Japanese maple. But we shall never see such a Prunen again.