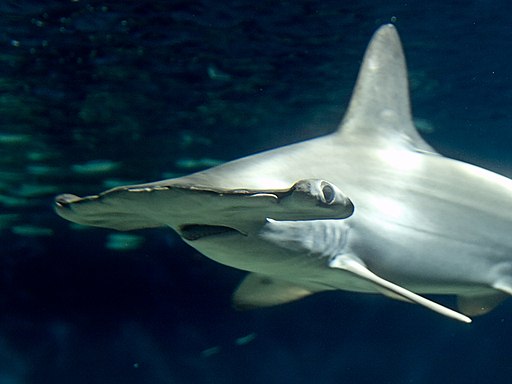

“Don’t die like an octopus, die like a hammerhead shark.”

One of my favourites from a recently encountered online stash of Maori proverbs, many of which I’d never heard before. Apparently octopusses (octopi? octopods?) give up if squirting ink at you didn’t scare you off, whereas hammerheads have fight in them practically all the way to the plate. (“I’ll bite your legs off!”)

Try another: “The kumara does not say how sweet he is.” This one brings up a difficulty with proverbs: you often want to… shall we say, apply them where they will do the most good, but the recipient does not always catch your drift. And sometimes it’s more embarrassing when they do. Ideally, they should catch your drift when they get home, as with the French esprit d’escalier, when you think of the perfect thing to say as soon as it’s too late to say it.

Trust the French to have a word for that. Just as the concepts other languages feel the need to have words for tell you something about them (see The Meaning of Tingo by Adam Jacot de Boinod), so the proverbs of other cultures give you a glimpse of their experiences and thought-processes. And sometimes you find out they were the same as yours. You would be surprised, for example, at how many cultures have proverbs linking the use-by-date of fish and guests.

Of course, just as surströmming and hákarl are not universally admired, so it is with proverbs. Take this, for example, from W. Somerset Maugham’s The Painted Veil: “A bird in the hand was worth two in the bush, he told her, to which she retorted that a proverb was the last refuge of the mentally destitute.”

Perhaps this explains the enduring popularity of what I now discover are called anti-proverbs. I had thought they were a sign of our sarcastic times, until I found this, from Oscar Wilde (1854-1900): “People who count their chickens before they are hatched act very wisely because chickens run about so absurdly that it’s impossible to count them accurately.” Hard to imagine the languid Oscar counting chickens himself – or having anything to do with chickens that didn’t involve a knife and fork – but he may well have a point there.

The anti-proverb most often quoted in my family is a much newer one, coined by Terry Pratchett in 1997 (in his novel Jingo). “Give a man a fire and he’s warm for a day, but set fire to him and he’s warm for the rest of his life.” And this illustrates the other problem with proverbs: even when they tell you something true, they aren’t necessarily helpful.

But today, at least, I can say I’ve learned something: do not go eight-legged into that good night…

But today, at least, I can say I’ve learned something: do not go eight-legged into that good night…