and also for cor, the Latin word for heart. Which is the origin of courage, in both senses of the word. Early Modern English – think Shakespeare or the King James Bible – used courage to describe a bewildering array of concepts circling around the core of a person: spirit, mind, disposition, nature, purpose, inclination, lustiness, vigour, wrath, pride and confidence. Overused? You bet.

But there is an older meaning. Middle English – think Chaucer or John Wycliffe’s New Testament- used it to mean “that quality of mind which shows itself in facing danger without fear; bravery; valour.” (Thank the SOD for the definition; it’s better than I could have done.)

But there is one point on which I would take issue with the SOD (and so, I think would Plutarch). There is more to courage than “facing danger without fear.” People – particularly young people, and particularly, it must be said, young men (I think it’s the testosterone that does it) – frequently do very dangerous things without the slightest hint of fear. Driving dangerously, jumping off cliffs, drinking more than is good for them, ingesting harmful chemicals…

This is not courageous. Stupid, yes. Courageous, no.

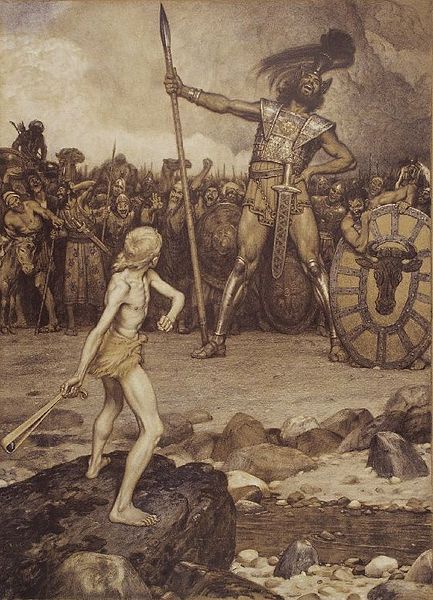

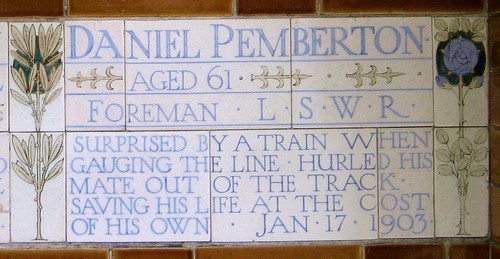

What makes the difference? Comte-Sponville thinks it’s whether you’re doing it for yourself or someone else. Myself, I think it’s a matter of why you’re doing it, and whether it or not it actually needs to be done. The same action can be pointlessly stupid or incredibly courageous, depending on your motivation. For example, jumping onto the train tracks to play chicken with a train is stupid, irresponsible and cruel (to the train-driver at the very least, and potentially to anyone who will miss you, and the person who will have to gather up the bits). Jumping on to the train tracks to save someone from a train, on the other hand, is immensely courageous.

But all this looks only at physical courage: braving physical danger or pain in the interests of what Plutarch would call a “just cause.” Physical courage can range from a child braving the needle for a vaccination, to the bravery of Edith Cavell, who risked her life to help the sick and injured in wartime, and in the end went calmly to her execution by firing squad.

Physical courage is not, however, the only kind; and it seems to me that the courage our world most suffers the lack of, is moral courage. The courage to do the right thing even if you do it alone. The courage to speak up when you know it’s going to cost you.

Whistle-blowers exhibit this kind of courage. They face ostracism, unemployment, imprisonment, exile, even death. But a whistle-blower is someone who is prepared to make personal sacrifices for the good of others, and that most certainly counts as courage.

And we need this kind of courage. It is the lack of this kind of courage that allows people to get away with abusing children, because other people don’t like to risk speaking up if they aren’t utterly sure. It’s the lack of this kind of courage that lets bullies and harassers run riot in organizations, because people are afraid of the backlash that will come from confronting or accusing someone in power. And so on and so forth.

To a certain extent, this is a cultural problem. We in the West have this odd prejudice against “tattle-tales” – as though there was somehow something shameful in bringing wrongdoing to light and seeking justice. It is seen as admirable to endure maltreatment without complaint, and to cover up for those who instigate the maltreatment. This is insane. Really. It’s practically Stockholm syndrome.

Of course, it isn’t phrased like that. We talk about not whingeing or whining or squealing, not being a cry-baby who has to ‘run to mama.’ But the result is the same. Those who are mistreated – or see others mistreated – and speak out, are treated as though they are the guilty ones. Because they are seen as the cause of the shame, because they brought it to light. This is the same logic that makes Indian women afraid to report rape, because they will be seen as bringing shame on their families, rather than bringing shame on their attacker.

Our world needs courage. And as John Stuart Mill noted, where there is eccentricity there is moral courage. So let us take heart, my dear eccentrics, and be courageous. Let us face necessary dangers unflinchingly, and seek justice uncowed by disapproval, ostracism or threat. Because nothing instils courage in others like an example they can follow, just as the ship in polar seas sails freely in the ice-breaker’s wake.