My Simplicity Heroes

I don’t really go in for hero-worship, but there are always going to be those people who make me think “Gosh! What a life! I wish I was a bit more like them…”

Number one on the simplicity charts is Jesus Christ (also the exception to the hero-worship clause). Jesus had so little that he once pointed out to a would-be follower that he didn’t own so much as a place to lie down. Foxes have dens, birds have nests – but if you’re going to follow me, don’t plan on being as comfy as them. Famously, he was so poor that when he died they had to borrow a tomb to bury him in.

Number one on the simplicity charts is Jesus Christ (also the exception to the hero-worship clause). Jesus had so little that he once pointed out to a would-be follower that he didn’t own so much as a place to lie down. Foxes have dens, birds have nests – but if you’re going to follow me, don’t plan on being as comfy as them. Famously, he was so poor that when he died they had to borrow a tomb to bury him in.

But he wasn’t a grim, joyless race-to-the-bottom kind of person either. He often got criticized by the establishment for going to parties (first miracle: turning about 600L of water into 600L of wine to spare some newlyweds the embarrassment of having under-catered their reception) and he once laid into his followers for lambasting a woman who poured a bottle of expensive perfume all over him. Thrifty it might not have been, but loving it was.

And while he might not have owned much but the clothes on his back, they weren’t the lowest rags available. He wore a seamless robe, which, as any weaver will tell you, is not the easiest thing in the world to make. Like the perfume, it was probably a gift. Medieval art suggests that it was made by Mary, although rather than getting into the technicalities of weaving, they just depicted her knitting in the round (using DPNs, not circulars).

I learned from his example that why is often at least as important as what; that good things are gifts to be enjoyed, but not expected; and that you should always give your grave back when you’re finished with it.

I learned from his example that why is often at least as important as what; that good things are gifts to be enjoyed, but not expected; and that you should always give your grave back when you’re finished with it.

Fast-forward a millennium or thereabouts and you encounter Francesco Bernadone, better known these days as St. Francis of Assisi. Francis was crazy in love with “Lady Poverty” (his term) and hey, people in love do weird things. Francis took a vow to never refuse to give anything that was asked of him “for the love of God” and his followers had the greatest difficulty in persuading him not to give poor people the clothes off his back.

When he retired from leading the order, the new leadership made him promise not to give his clothes away any more – it looked bad, having your founder running about in his underwear – and Francis obediently promised. So the next time he encountered a beggar wearing less than him, he sorrowfully informed the fellow that he couldn’t give him his clothes – and then suggested the beggar should mug him. Possibly the first recorded instance of legalism being used in a good cause.

I learned from Francis that having little or nothing can be as full a life as having much – or even fuller. As he pointed out, as soon as you start having stuff, you start worrying about people nicking it. No stuff? No worries.

#3 on the list is a group rather than a person: the Quakers, a.k.a. the Society of Friends. (Mostly the historical Quakers. Richard Nixon, not so much.) Unlike #1 and #2, they didn’t generally divest themselves of all possessions, up to or including their clothing. They took a slightly different approach. Instead of reducing themselves to a level of poverty where they were dependent on the kindness of others, they aimed to be the ones whose kindness others could depend on.

In order to be able to be generous, they worked hard and developed businesses along sound ethical lines. Many were wealthy – bankers, manufacturers – but unlike the wealthy of today, they shunned luxury and conspicuous consumption, believing that no one was superior to anyone else and it was shameful to act (or dress) as though you were. Instead, they poured their time and resources into social justice causes, such as the reform of inhumane conditions in prisons and – famously – the abolition of slavery.

However plain – or rather, Plain Quakers were, they weren’t against the good things of life (apart from being teetotal). They were industry leaders in the chocolate business – need I say more? Plainness was a hallmark of the Quaker, yes, but so was quality. A Quaker would, for example, infinitely prefer to wear the same plain, good quality garment for years, than to have a never-ceasing cycle of cheap fashionable tat filling their wardrobe.

However plain – or rather, Plain Quakers were, they weren’t against the good things of life (apart from being teetotal). They were industry leaders in the chocolate business – need I say more? Plainness was a hallmark of the Quaker, yes, but so was quality. A Quaker would, for example, infinitely prefer to wear the same plain, good quality garment for years, than to have a never-ceasing cycle of cheap fashionable tat filling their wardrobe.

The point for the Quakers was not that it was wrong to spend money, or even to spend money on things for yourself. The point was that it was wrong to spend money on things for yourself that you didn’t need, when others didn’t have the things that they needed.

I learned from the Quakers that #1’s command to “Love others as you love yourself” can be taken as a practical instruction for living; that living simply so that others can simply live really does make a difference; and that being thought odd is no barrier to making change in your world.

History bears witness that their simplicity brought great good to many. I hope that one day that can be said of me.

Peeling Back the Layers

As habitual readers of this blog will know, I spent the best part of February decluttering and purging my home. The Grand Purge, I called it. Boxfuls of stuff left the house, destined for charity shop, recycling station or (alas) dump.

Then, with a sigh of relief, I got back to my main work: writing. (For those of you with an interest in things writerly, I’ve been focusing my rewriting work on my weak point: character, using Jeff Gerke’s Plot Versus Character). The job, so I thought, was pretty well done.

Then we went away for Easter weekend, and when I came back, I seemed to see with new eyes.

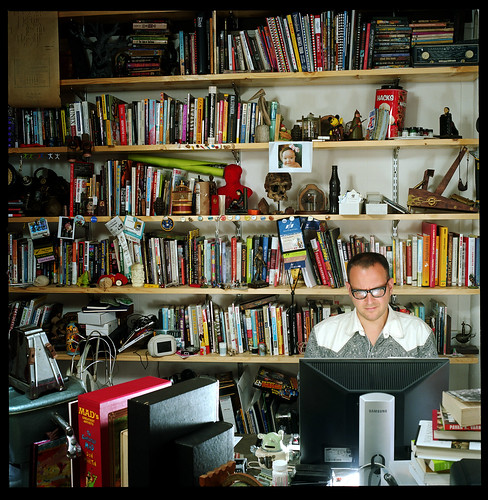

The house was still full. Cluttered, even. I’ve never thought of myself as being over the top when it comes to possessions, at least on a Western scale – our kitchen bench isn’t piled high with appliances we don’t use; the bathroom isn’t stuffed with half-used lotions and potions, and our sporting equipment consists, in toto, of one petanque set, a frisbee and a boomerang.

But it still seemed like too much. Much too much, in places. I realized, with sinking heart, that I had only removed the outer layer.

I found myself looking at the shelves and wondering what would make the cut if, instead of keeping everything that I didn’t dislike, I only kept the things I specifically wanted. Only the favourites. Immediately reasons not to leapt to mind: that one was a gift; this other one is part of a set; those ones there you might just not be in the mood for at this moment…

I found myself looking at the shelves and wondering what would make the cut if, instead of keeping everything that I didn’t dislike, I only kept the things I specifically wanted. Only the favourites. Immediately reasons not to leapt to mind: that one was a gift; this other one is part of a set; those ones there you might just not be in the mood for at this moment…

I had thought that I found getting rid of things easy, but it turns out that that was simply because I had far more than I actually even wanted, let alone needed. (Horrifying thought.)

I want to live a simple life, and the cost of that is getting rid of things. Even things which I quite like, in a way; things I’d be happy to keep having, but am not, in point of fact, attached to. Perhaps they are attached to me, though, because they’re quite hard to shake.

It is work getting rid of things. Not just the physical work of moving things from point A (your house) to point B (anywhere that isn’t your house), but the psychological effort of disrupting the usual, uprooting the habitual, and leaving only the intentional behind.

It’s frightening, in a way, and it shouldn’t be. Who am I without all these familiar things? The same person I am with them, surely, only with less stress and more space. Less stuff looming over my shoulder…

But since my work would undoubtedly suffer if I took another four weeks off to focus on de-stuffing, another method must be found. This time, I am thinking of working backwards: starting with the desired result, and doing what is necessary to reach that point.

But since my work would undoubtedly suffer if I took another four weeks off to focus on de-stuffing, another method must be found. This time, I am thinking of working backwards: starting with the desired result, and doing what is necessary to reach that point.

Of course, this is slightly complicated by (still) not knowing what size house we’re going to wind up in, and therefore how much stuff will need to be removed in order to create the desired degree of spacious unclutteredness. And since I tend to be a big-picture vague-on-details person, I need to come up with some concrete specifications of what part of the work I’m going to do when, or it will only happen in fitful frustrated starts and stops – ultimately patchy and unsatisfactory.

But there we are. As Pasternak so rightly observed, “Living life is not like crossing a meadow.”