Spending one’s days pretending to be a small piece of plant material doesn’t seem like much of a lifestyle aspiration to me (though there are moments…). Stick insects, on the other hand, seem to have a passionate devotion to the artistry required to really get inside the part of A Stick.

So here for your enjoyment are ten fascinating facts about the wacky, wonderful stick insect.

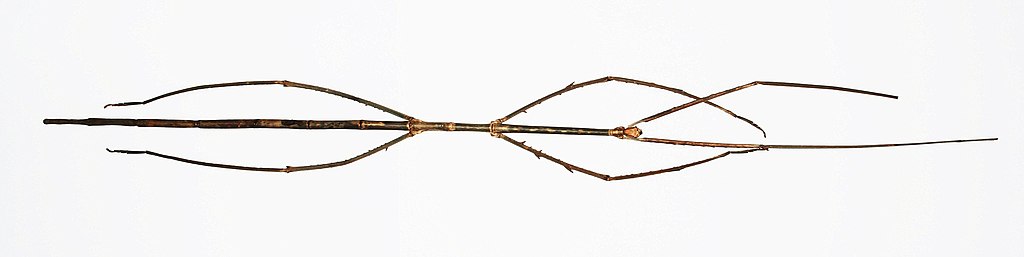

1 The largest stick insect is the Phobaeticus chani, measuring up to 56.7cm long (that’s 22.3 inches for the imperialists). That’s including the legs, but even without them it’s 35.7cm (14.1 inches). That’s so big I feel like it should be called a branch insect, although its actual non-Latin name is “Chan’s Megastick”, which seems fairly appropriate, and really rather cool.

2 The rarest stick insect is the Lord Howe Island Stick Insect, which was thought to be extinct (until it moved…). It’s also known as the tree lobster, because – well, imagine a smallish lobster in a tree and you’ve pretty much got the Lord Howe Island stick insect. I dare say living on a “volcanic remnant” in the middle of the sea means there isn’t so much pressure to pass yourself off as a bit of shrubbery, though passing yourself off as seafood doesn’t seem like a much better idea.

Side note: why do people eat lobsters? They’re related to slaters, for pity’s sake. Only better armed. They’re the angry weaponized woodlouse of the sea. Moving on…

4 Some sorts of stick insect can drop one of their independent legs when attacked, leaving it behind as a decoy/distraction/sacrifice, while the five other independent legs all decide to run away with the body. Young ‘uns are usually able to grow a replacement limb, but this ability fades with age.

5 Some sorts of stick insect get really Method about impersonating vegetation, developing ridges to look like leaf veins (yes, despite the name, some pretend to be leaves instead of sticks), brown spots and even a bark-like texture. Some can even change colour to blend in with their surroundings (unlike chameleons, who are basically nature’s mood rings).

7 To avoid dying out in the event of the blokes not being able to spot them, the ladies have developed the ability to produce sprogs all on their own. Of course, they can only produce females, which leads to the slightly awkward situation where the males of some species have yet to be located, if they do indeed still exist.

Weirdly, there’s a New Zealand species which was introduced to the UK some years back, of which no male has ever been discovered in New Zealand – and yet they have discovered one in the UK. Mysterious… And since the involvement of a male only lowers the proportion of resulting female sprogs to 50%, stick insects have a worse gender ratio than China (albeit in the opposite direction).

And if the tasty-looking egg is scarfed down by a passing bird, not to worry – they have a protective coating which means they will emerge unharmed out the other end of the avian digestive tract. One can only hope they never hatch halfway down, as that would be Unpleasant For Everybody.

9 Once de-egged and stick/leaf shaped, they have a whole battery of useful tactics to employ against predators. Being hard to spot is, of course, their first line of defense. Swaying gently like a twig in the breeze is a popular approach, albeit more convincing if there is a wind in the garden. Locking one’s legs to one’s sides and dropping to the leaf litter like a snapped twig is also an excellent escape strategy.

Mugger: gimme your bag!

You: blaaargh!

Mugger: screams, runs away wiping ineffectively at self.

Some species even have glands which allow them to deploy a chemical spray, although this backfired somewhat for one Papua New Guinean species when the local people realized it made a great antibacterial spray for skin infections (shake insect well before applying).

10 Last, but not least, is the reason these weird-looking creatures are so beloved – even kept as pets in many parts of the world – despite being rubbish at pest control and being leaf-eaters themselves. Unlike the much-hated myriads of bugs, grubs etc which will not demean themselves by taking more than a few bites out of any one leaf, stick insects will patiently and tidily munch their way through a whole leaf before starting on another.

I would like to say that this is what made me decide to exercise clemency on the several baby stick insects I found in the thorn tree when I went to strip the severed branches, but the truth is that there’s something unassailably cute about an inch-long tiny green wisp of insecthood waving its dill-like legs in the air and pretending to be the world’s smallest twig. On your glove.

And your pruning saw.

And your secateurs.

And now in an assortment of other trees and shrubs in the garden. Wave on, little friends.

Hehehe! 😀 Thanks for the laughs – I needed that!

You’re welcome! Always happy to provide a laugh. 🙂