Fame is a chancy thing. It is well known for flitting off the second your back is turned (nothing so fickle as fame) but it is also fond of landing on people when they least expect it – or leaping out on them from an unanticipated direction.

Of course, most of us will never be famous at all (there isn’t room) but some who become famous do so for entirely unanticipated reasons; reasons which sometimes eclipse a fame-worthy effort in another direction.

Of course, most of us will never be famous at all (there isn’t room) but some who become famous do so for entirely unanticipated reasons; reasons which sometimes eclipse a fame-worthy effort in another direction.

Take Margaret Mead for example. She is perhaps more widely known for the quote “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has,” than for her work as a cultural anthropologist. This is almost painfully ironic, considering that there is no proof that she ever said or wrote it.

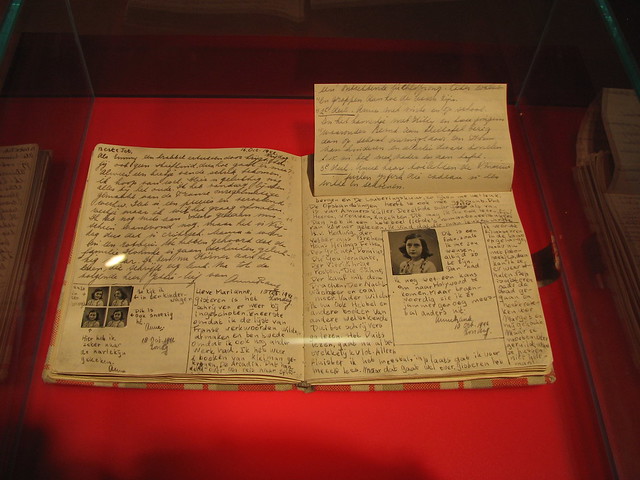

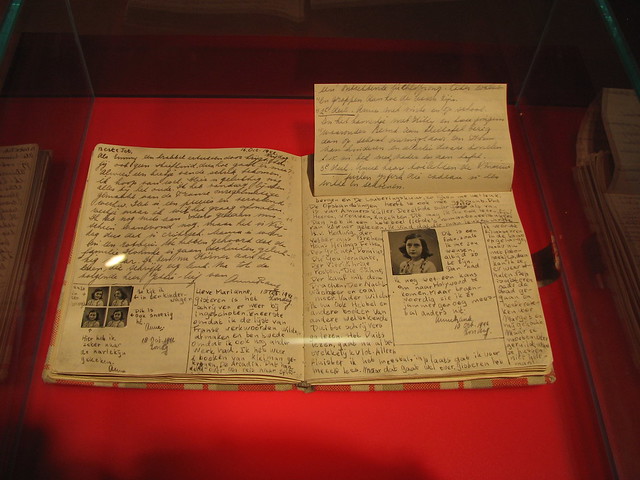

To take another example, from The Illustrated History of the Housewife by Una A. Robertson, “Scotland’s Lady Grisell Baillie, of Mellerstain, near Kelso, is now better known through her book of domestic accounts than for her childhood heroism in saving her father’s life.” Thus proving that even the most dramatic of acts can be overlooked in retrospect, particularly if you leave behind solid documentary evidence of something else. (Another good argument for keeping a diary: distracting posterity from those things you’d rather it forgot.) Indeed, it is possible to become famous simply because you kept a diary.

Who knows? Perhaps Richard Dawkins may someday be remembered as the coiner of the word-of-the-age, ‘meme’ – meaning a cultural thing that is copied or transmitted in a similar way to biological data such as genes. He is, after all, a biologist – despite his outspoken opinions on other things, such as reading fairy tales to one’s children.

Who knows? Perhaps Richard Dawkins may someday be remembered as the coiner of the word-of-the-age, ‘meme’ – meaning a cultural thing that is copied or transmitted in a similar way to biological data such as genes. He is, after all, a biologist – despite his outspoken opinions on other things, such as reading fairy tales to one’s children.

To be fair, while he initially said it was “pernicious to inculcate into a child a view of the world which includes supernaturalism,” he then decided that perhaps fairy tales encouraged the “spirit of scepticism” in children and were therefore permissible. This all comes rather oddly from someone who claims that “there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.” Pitiless he may or may not be, but he certainly doesn’t seem indifferent.

Dawkins has had some bad press in the past, so perhaps it would be only kind to begin associating him with that queen of memes, the captioned kitty. Considering his opinions on, for example, Down’s Syndrome, this would seem a good place to start:

For another example of unintentional fame, take Edward Bulwer-Lytton. He might have thought he would achieve fame for his political achievements – he was Secretary of State for the Colonies at a time when Britain was by no means short of them – or for turning down the position of King of Greece. He probably dreaded the thought of becoming famous for inspiring Wilkie Collins’ novel The Woman in White, by having his (sane) wife committed to an insane asylum when she campaigned against his election to Parliament. He may have hoped that he would become famous for his novels, but probably not the way it happened: his fame has been almost entirely eclipsed by one of his opening lines.

For another example of unintentional fame, take Edward Bulwer-Lytton. He might have thought he would achieve fame for his political achievements – he was Secretary of State for the Colonies at a time when Britain was by no means short of them – or for turning down the position of King of Greece. He probably dreaded the thought of becoming famous for inspiring Wilkie Collins’ novel The Woman in White, by having his (sane) wife committed to an insane asylum when she campaigned against his election to Parliament. He may have hoped that he would become famous for his novels, but probably not the way it happened: his fame has been almost entirely eclipsed by one of his opening lines.

It was a dark and stormy night… Of course, that isn’t so bad, if you’re the first to write it (which he was). If only he had left it at that, instead of extending the sentence to read “It was a dark and stormy night; the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the housetops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.”

This subsequently inspired some of the right-thinking sort to start a competition for execrable opening sentences: The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest. This year’s submissions close next week (Thursday June 30th), so why not have a crack at it? If, like Edward B-L, you can become famous for a single line, why bother writing the rest of the novel?

This subsequently inspired some of the right-thinking sort to start a competition for execrable opening sentences: The Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest. This year’s submissions close next week (Thursday June 30th), so why not have a crack at it? If, like Edward B-L, you can become famous for a single line, why bother writing the rest of the novel?

The moral of the story (yes, sorry Mr Dawkins, this is one of those pernicious stories that have morals to them) is that it pays to be careful what you do, or write, or say, because you may become famous for something you didn’t mean to. Or something you didn’t even mean. Or even, like Margaret Mead, something you didn’t even say, but there is (alas!) not much you can do about that.