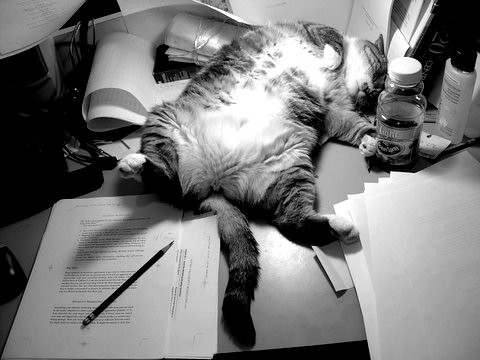

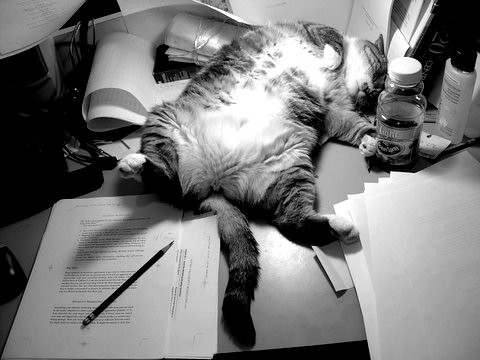

It seems to be a quirk of creative types to be accoutred with a cat – or several. Writers are particularly prone to cats – Ernest Hemingway’s collection of polydactyl cats being perhaps an extreme example – but the link is well-documented in both word and image, albeit not entirely understood.

“A catless writer is almost inconceivable,” says Barbara Holland. “It’s a perverse taste, really, since it would be easier to write with a herd of buffalo in the room than even one cat; they make nests in the notes and bite the end of the pen and walk on the typewriter keys.” But not all writing cats are so unhelpful. Kerry Greenwood says she has “a censorious cat called Belladonna who supervises the process and won’t let me write more than two hours without a break. She slyly hits the caps lock with her little black paw. Thus I am saved from carpal tunnel syndrome and she is well supplied with cat treats (those expensive green ones).”

It’s the same with knitters. As Stephanie Pearl-McPhee notes in her book At Knit’s End, “the tendency to be accompanied by a cat is an oddity among knitters that cannot be explained…. Most cats have a thing about knitting. They are honor sworn to pester knitters and be involved in knitting as much as possible. They lie on patterns, play with balls of yarn, bat at the end of a moving needle, and given two seconds of opportunity, will spread themselves all over your knitting, intentionally shedding as much fur as possible. When selecting a cat to share my life and knitting with, I will consider choosing one whose fur doesn’t contrast with my favorite color yarn.”

My cats know better than to play with an active ball of yarn (though you can see the temptation growing on them as they stare at it) but they do like to be in a lap that has knitting on it. The more mature of the two is happy to just sit alongside the knitting (she’s the one who’s a fibre snob), but the junior seems to think his life will not be complete until he has somehow climbed into the needle-portal and merged his dimensions with those of the knitting. I live in fear of ending up with a Klein-bottle-sock-cat (which isn’t a Dr. Seuss book, but should be).

Then there are sewing cats. Cats love sitting on rustly paper. Newspapers are better than books or magazines, and the delicate tissue of pattern paper is even better. Add the plethora of textures afforded by fabrics, and you have an irresistible cat-magnet. Leimoni Oakes, aka the Dreamstress, has a whole category of blog posts dedicated to the ‘assistance’ of her sewing-cat Felicity. The blog at Cation Designs has both a tag and a tab about the dedicated sewing-cat and model Walnut.

There are also cats who dwell with artists, no doubt taking every opportunity to filch food from still life compositions, leave little painty footprints about the premises, and bat shards of stone across the floor to where an unsuspecting foot will encounter them. (Cats are very thoughtful in that respect).

Doubtless there are many more examples of cats and their creatives, which simply don’t happen to have come to my notice (but please mention them in the comments).

Whatsoever your hand findeth to do, you can pretty much guarantee that your cat will climb into it. Knitting? Yes please. Sewing? Let me help you pin that down (with my claws). Reading? I’ll hold the book open for you (by lying on it). Hanging out the laundry? I’ll turn unintentional back-flips while trying to uproot the washing-line pole (since you won’t let me play with the pegs). Pruning? I’ll hide in the bush and dab at the secateurs as they come past. Playing pétanque? Let me lurk on the sidelines and dash madly into the path of the steel balls as you hurl them. Cooking? The floor will seethe with cats at every turn, especially if you’re cooking anything animal based (although one of our cats will eat bits of raw kale that have fallen on the floor – if she thinks you’re not looking).

Why it is that cats do this is unclear. Boredom? It’s hard to bore an animal that is content to spend its days eating, sleeping and licking itself. Are they offering support? Are they offering – or seeking – companionship? Or do they merely wish to come between their person and anything that might look like it’s getting more attention than they are? Whatever the reason, it seems the attentions of a determined cat are inescapable, so we might as well accept them for the furry little joy-bringers they are, and do our best to get on with life despite their ‘help’.